-

Cultural Diversity and the National Trust movement

Posted on May 21, 2014 At the recent Barbados Conference, Tracey Todd of Middleton Place, South Carolina, introduced delegates to “High on the Hog” by food historian Jessica Harris and in particular a trip she takes with her mother to Houmas House, near New Orleans. One of a string of former plantations along Louisiana’s River Road, the estate bears witness to a cruel history. Harris, who is black, speculates aloud that much of the place was built by slaves. The remark draws an unexpected response. “What artistry,” her mother says. “What beauty they created for people who thought we were nothing but goods, not even human beings!”

At the recent Barbados Conference, Tracey Todd of Middleton Place, South Carolina, introduced delegates to “High on the Hog” by food historian Jessica Harris and in particular a trip she takes with her mother to Houmas House, near New Orleans. One of a string of former plantations along Louisiana’s River Road, the estate bears witness to a cruel history. Harris, who is black, speculates aloud that much of the place was built by slaves. The remark draws an unexpected response. “What artistry,” her mother says. “What beauty they created for people who thought we were nothing but goods, not even human beings!”This really got us thinking. Many Trusts have wrestled with questions of cultural rights, access to heritage, community involvement, whose heritage, dialogue and understanding, and this debate underpinned INTO’s 2013 Entebbe Declaration, as telling forgotten and sometimes shameful stories is essential to understanding our future.

Last year, I was invited to speak at a Brunel University seminar “Heritage, diversity and the legacies of empire” and this blog is taken largely from those notes.

Last year, I was invited to speak at a Brunel University seminar “Heritage, diversity and the legacies of empire” and this blog is taken largely from those notes.Britain today is a multi-cultural country and one in six of the population is non-white. However, membership of the National Trust is still predominantly white, elderly and middle class. The Trust as a private charity is not obliged – in the same way as state counterparts English Heritage, for example – to hit particular government diversity targets, but it has recognised that as an organisation it has to make every kind of visitor – whatever their background – feel comfortable and feel it is their property, or their bit of countryside. Over the past few decades, the Trust has taken steps to reflect the diversity of the communities around the places in its care, but it recognises that it can be hard to sustain such projects and there is much more to be done.

When the National Trust was established in 1895 it focussed on protecting open space and encouraging the urban poor to enjoy it. It moved onto to collecting examples of rural life (post offices, villages) that were being encroached upon by the expansion of the towns, becoming the ‘saviour’ of the country house estate after the Second World War. In the 1960s, the Trust began to champion more environmental causes with the launch of Enterprise Neptune in 1965. And then in the last few decades, it began focusing on social history, telling the stories of ‘below stairs’, taking on the houses of the Beatles in Liverpool, a workhouse, the Back-to Backs in Birmingham and developing a much more ‘open arms’ approach.

When the National Trust was established in 1895 it focussed on protecting open space and encouraging the urban poor to enjoy it. It moved onto to collecting examples of rural life (post offices, villages) that were being encroached upon by the expansion of the towns, becoming the ‘saviour’ of the country house estate after the Second World War. In the 1960s, the Trust began to champion more environmental causes with the launch of Enterprise Neptune in 1965. And then in the last few decades, it began focusing on social history, telling the stories of ‘below stairs’, taking on the houses of the Beatles in Liverpool, a workhouse, the Back-to Backs in Birmingham and developing a much more ‘open arms’ approach.The Trust has been criticised in the past for promoting a nostalgia for the specifically national, aesthetically pleasing and grand scale, but it is working hard to broaden participation and avoid tokenism.

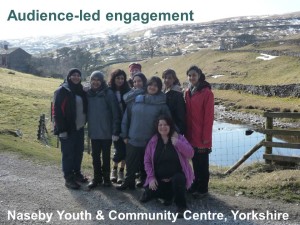

Audience-led engagement

The Trust is committed to getting people outdoors and enjoying nature and is facing up to the challenge of extending access to the British countryside to immigrant and migrant communities. In Birmingham, the Trust has developed community partnerships that have raised its profile at local level and enabled the recruitment of new volunteers who reflect the population living near its sites.

One partnership was with a local Youth & Community Centre, which approached the Trust to do a residential volunteering weekend somewhere outside of Birmingham for a young Asian girls group. The group were keen to choose the right place, as it would be their first, and possibly only, opportunity to volunteer outside of their home city. 30 Trust properties offered to support the visit, and the group selected the Yorkshire Dales as their destination.

One partnership was with a local Youth & Community Centre, which approached the Trust to do a residential volunteering weekend somewhere outside of Birmingham for a young Asian girls group. The group were keen to choose the right place, as it would be their first, and possibly only, opportunity to volunteer outside of their home city. 30 Trust properties offered to support the visit, and the group selected the Yorkshire Dales as their destination.The outdoor weekend included tree planting and maintenance work in the surrounding woodland. However, it wasn’t all hard work and, as well as a picnic by a beautiful stream, the young women enjoyed having a go at geocaching. This demonstrates how this group was able to get involved in the Trust for the first time, leaving a lasting impression on both the young women and the NT.

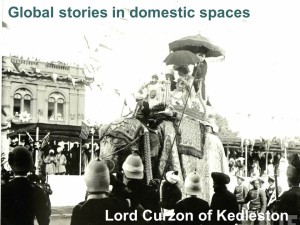

Global stories in domestic spaces

In London, the population, social and demographic mix is very different from anywhere else in the country. National Trust membership is comparatively low, the Trust’s traditional offer of houses, gardens and open space is not strong, and the competitive offer is very compelling, and often free. But the Trust’s eight properties are working hard. And celebrating cultural diversity is very much at the heart of what they do.

575 Wandsworth Road is a modest early 19th century terraced house. On the outside. Inside, Kenyan-born poet and British civil servant, Khadambi Asalache, transformed his home into a work of art by hand-carving exquisite fretwork patterns and motifs. Truly a global story in a domestic setting.

Osterley Park in West London provides a much needed open space to the surrounding communities, and recently hosted an oral history event for local Hounslow residents as part of preparation for an exhibition on the domestic history of the East India Company. There are significant Sikh and Tamil communities living near Osterley, and the event sought to explore the connections between their heritage and the collection at Osterley, which is rich in Asian objects.

Osterley Park in West London provides a much needed open space to the surrounding communities, and recently hosted an oral history event for local Hounslow residents as part of preparation for an exhibition on the domestic history of the East India Company. There are significant Sikh and Tamil communities living near Osterley, and the event sought to explore the connections between their heritage and the collection at Osterley, which is rich in Asian objects.[Interestingly, Osterley was also used as a film venue for the film Amazing Grace, about anti–slavery pioneer William Wilberforce!]

There is a tendency to think of Empire as something that happened ‘over there’ but as with many things, it is not possible to tell one single story about our colonial past.

Lord Curzon of Kedleston

Lord Curzon’s story serves to illustrate this. Whilst Viceroy of India, Curzon successfully fought to save much of the country’s heritage, including the Taj Mahal. On his return to Britain he sought to do the same here as one of the sponsors of the 1913 Ancient Monuments Act. Not only did he famously save Tattershall Castle from the brink, he also gave Kedleston Hall with its treasure trove of fascinating objects acquired on his travels in Asia to the National Trust. And this today now provides a focus for connecting with the local Asian community in Derby.

Lord Curzon’s story serves to illustrate this. Whilst Viceroy of India, Curzon successfully fought to save much of the country’s heritage, including the Taj Mahal. On his return to Britain he sought to do the same here as one of the sponsors of the 1913 Ancient Monuments Act. Not only did he famously save Tattershall Castle from the brink, he also gave Kedleston Hall with its treasure trove of fascinating objects acquired on his travels in Asia to the National Trust. And this today now provides a focus for connecting with the local Asian community in Derby.So, the will is there and so are many of the other building blocks – the Trust and its properties are very good at audience segmentation and understanding that different things matter to different people. They are rising to the challenge to reach out to communities and volunteers, encourage people to get actively involved in the Trust’s work and places, and inspire people who’ve never visited NT places to engage and find relevance to their own lives.

The bigger picture

Even in its infancy, the National Trust was part of a wider movement (both in the UK with the Commons Preservation Society [1865] and William Morris’s Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings [1877], and overseas) to appreciate nature and beauty. The Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments (Fortidsminneforeningen) was established in 1844 by artists who “discovered” Norway’s cultural heritage during academic excursions to rural districts and valleys. Whether or not the Trust’s Founders knew about this group, I don’t know but I do know that they were greatly influenced by the US Land Trust movement and the Trustees of Reservations in Massachusetts, which was established in 1891.

Even in its infancy, the National Trust was part of a wider movement (both in the UK with the Commons Preservation Society [1865] and William Morris’s Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings [1877], and overseas) to appreciate nature and beauty. The Society for the Preservation of Norwegian Ancient Monuments (Fortidsminneforeningen) was established in 1844 by artists who “discovered” Norway’s cultural heritage during academic excursions to rural districts and valleys. Whether or not the Trust’s Founders knew about this group, I don’t know but I do know that they were greatly influenced by the US Land Trust movement and the Trustees of Reservations in Massachusetts, which was established in 1891.Since then, the National Trust movement has grown to include a range of countries from Australia, Bermuda and Canada through Korea, Malta and the Netherlands to Taiwan, the United States and Zanzibar! Each organisation is different but they share similar goals, legal constitutions and structures, and for over 30 years have been coming together under the umbrella of the International Conference of National Trusts to share information and best practice, to develop solutions to common problems and to show solidarity with other members of the movement. INTO was established in 2007 as a permanent focal point for the global federation.

National Trust neo-colonialism?

As I said, over the past 120 years, the National Trust has grown into the largest conservation charity in Europe. As it helped establish National Trusts in other countries along the way, rather haphazardly and often through social and personal connections, it must have been tempting to take a more paternalistic approach. But unlike its imperial antecedents, the National Trust was not something that was imposed from London and each country adapted the concept to its local situation.

And so the very existence of National Trusts across the overseas territories and Commonwealth could perhaps be seen as a legacy of empire?

Legacy of Empire: Architecture

Legacy of Empire: ArchitectureIt is impossible to generalise about British colonial heritage but one thing is for sure is that it evokes mixed feelings, from pride and wonder to guilt, shame and denial.

Here in Myanmar, the newly formed Yangon Heritage Trust is battling to protect the city’s unique colonial heritage, saved from the fate of other Asian cities due to the country’s relative isolation over the past 50 years.

One of their strategies is to encourage international banks who once had their headquarters in splendid historic palaces (Hong Kong Shanghai Bank, Chartered Bank, and Lloyds) to return to these spaces and give them a new lease of life.

Legacy of Empire: Mistrust

It is probably no surprise to hear that the current economic and political situation presents significant challenges to the National Trust of Zimbabwe which manages a number of natural heritage sites, a museum and its flagship property, La Rochelle.

It is probably no surprise to hear that the current economic and political situation presents significant challenges to the National Trust of Zimbabwe which manages a number of natural heritage sites, a museum and its flagship property, La Rochelle.This is the home of Sir Stephen and Lady Courtauld who, although establishment figures, were renowned liberals and championed the rights of indigenous people. The first ZANU constitution was even written at La Rochelle.

However, as in other post-colonial societies, the National Trust is viewed as ‘old Zimbabwe’ and is mistrusted by government. Its supporters are so poor and disenfranchised that they cannot afford to preserve their heritage – black or white – and live in constant fear of requisition. The Trust is beginning to involve local communities and a recent visitor to La Rochelle reported that a group of about 35 ladies from the Mutare Anglican Church had come for a Braai (barbecue) and to meet and talk.

Legacy of Empire: Education

Legacy of Empire: EducationWhen considering whether the British Empire was a force for good or not, education is often cited as one of the positive legacies. In India, the combination of a British education and the Indian caste system led to the development of the colonial middle class in the mid-19th Century which has spawned much of India’s current metropolitan middle class, numbering around 250 million today.

INTACH, the Indian National Trust, still prioritises education with its school Heritage Clubs and outreach to young people and by appealing to its middle class supporters, is able to raise funds and build awareness and civic engagement for its heritage projects.

Legacy of Empire: Empowerment

INTO has learned from the legacies of Empire the importance of letting others take the lead. The Empire was probably more pluralistic than my simple interpretation, but it was ruled from London. The National Trust does not seek to replicate this by establishing mini-fiefdoms across the globe nor by imposing its knowledge and experience on the newer members of the family. It has as much to learn as others.

Our last INTO Conference was held for the first time on the continent of Africa, hosted by INTO members the Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda. This was an excellent opportunity to examine the National Trust model from beyond the British prism. The conference brought together practitioners from across the globe to explore the diversity of relevance of heritage from a people’s perspective, with an emphasis on the connection between the tangible and intangible heritage, whilst at the same time strengthening INTO’s work across the world, but particularly in ‘the South’ where cultural and historical sites are at increasing risk.

Our last INTO Conference was held for the first time on the continent of Africa, hosted by INTO members the Cross-Cultural Foundation of Uganda. This was an excellent opportunity to examine the National Trust model from beyond the British prism. The conference brought together practitioners from across the globe to explore the diversity of relevance of heritage from a people’s perspective, with an emphasis on the connection between the tangible and intangible heritage, whilst at the same time strengthening INTO’s work across the world, but particularly in ‘the South’ where cultural and historical sites are at increasing risk.One of the projects we learned more about involves small and innovative museums. The CCFU works with around 20 ‘Community Museums’ to build capacity and awareness, including the Isingiro Women’s cultural group on a remote hill in south western Uganda, which has assembled artefacts of their traditional culture and visits schools and public gatherings to exhibit them.

And in Kabale, Edrisa is a museum where a retired teacher has reconstructed a traditional hut and shrine complete with all interior fittings and furniture, that is open to tourists and school children. The museum also has a craft shop and a small restaurant. These initiatives are often undertaken by individuals or small groups in extremely difficult circumstances and with very little funding but demonstrate great enthusiasm for the right to appreciated and enjoy the diversity of their cultural heritage.

In conclusion, there is a clear need to strike a balance between remembering our imperial past (good and bad) and understanding its impact on our multi-cultural present, which might mean an adjustment to how we think about the heritage of different cultural groups, manage their diversity and recognise cultural rights. Strengthening international co-operation and solidarity is an important means by which to achieve this so I am very glad to support World Day for Cultural Diversity today.

44 (0)20 7824 7157

44 (0)20 7824 7157